Is it possible that existence is our exile and nothingness our home? —Emil Cioran

A foreigner visiting Oxford for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments and administrative offices. He then asks ‘But where is the university? I have seen where the members of the colleges live, where the registrar works, where the scientists experiment and the rest, but I have not yet seen the university in which reside and work the members of your university.’

The visitor's error is presuming that a University is part of the category units of physical infrastructure rather than that of an institution. Gilbert Ryle uses the above anecdote in his book The Concept of Mind to illustrate his idea of a Category Mistake, an error in which things belonging in one category are impossibly assigned characteristics belonging to another category.

René Descartes held that mind is a nonphysical — and therefore, non-spatial — substance, and was the first to formulate the mind–body problem in the form in which it exists today. Ryle alleged that it was a mistake to treat the mind as an object made of an immaterial substance because predications of substance are not meaningful for a collection of dispositions and capacities – in other words, Cartesian mind-body dualism is a category mistake because it confuses the category things of substance with the category behavior (or, side-effects).

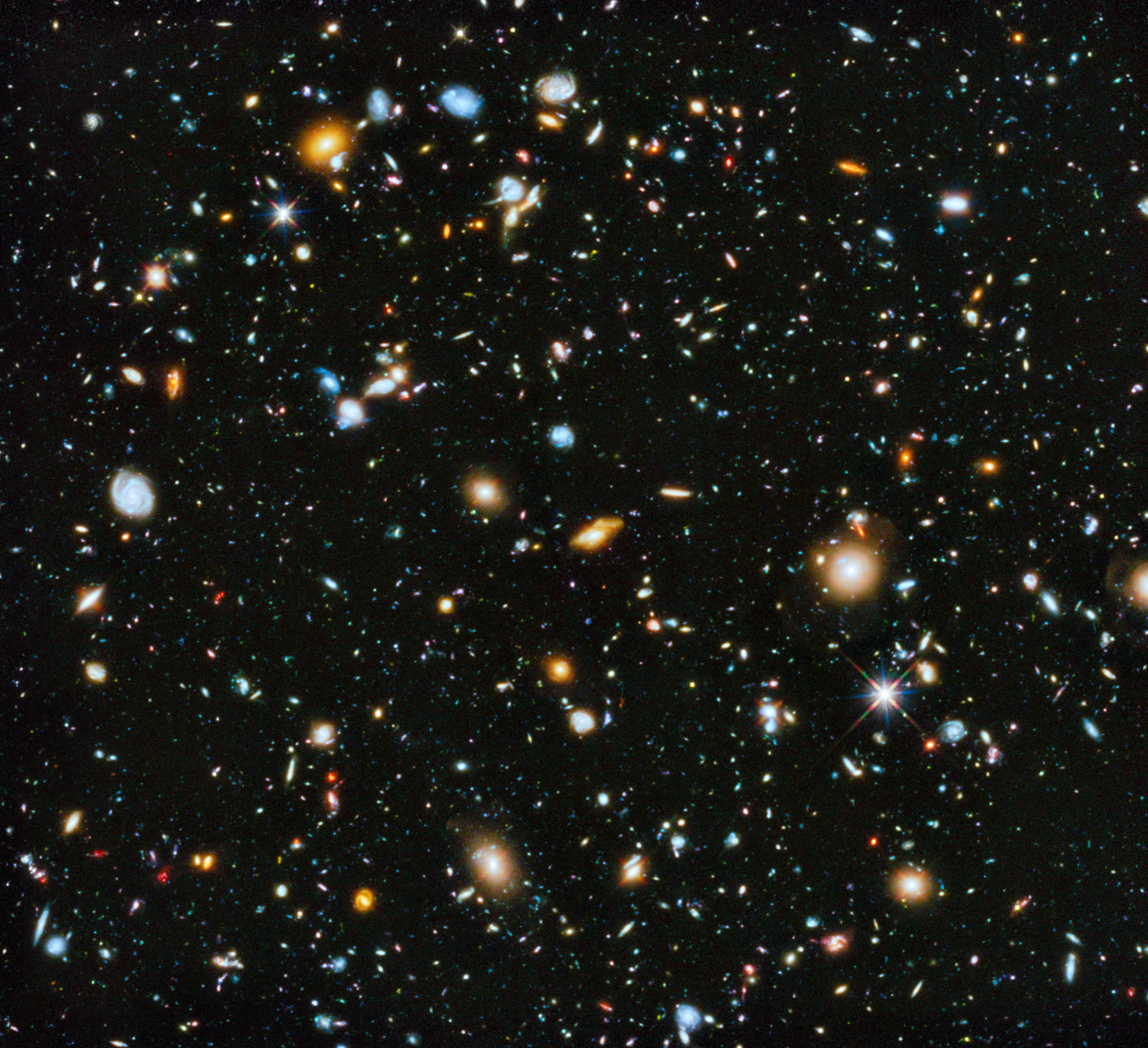

Dartmouth’s ICE hosted a lovely conversation on the nature of reality between Alan Wallace, a Buddhist monk and scholar, and Sean Carroll, a well-known theoretical physicist. Carroll argues that, through scientific inquiry, a comprehensive understanding of reality is within our reach. Wallace argues that such a materialist account of our Universe fails to fully account for both the complexities of the human mind and the world outside it. Carroll rejects the specialness we grant ourselves as humans. He invokes the image of the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field in order for us to appreciate the vastness of the universe – two trillion galaxies in the observable universe by current estimates, on average a hundred billion stars per galaxy. Carroll asserts – and acknowledges this to be a cheap argument – that the visceral claim that consciousness must be an essential part of all this seems very backward. In trying to juxtapose our anthropocentric obsession with introspection against the backdrop of an endless multiverse (very evocative indeed) he also inadvertently exposes the absurdity of existence which then begs the question. Towards the end of the conversation Wallace asserts that we have to take first person experience more seriously, our scientific way of observing our mind is not scientific: that refined developed introspection – in other words, empirical observation, science’s primary tool in observing phenomena – plays no role whatsoever in the modern scientific study of the mind. He doesn’t need any appeal to dualism in order to justify introspection of the mind (distinct from the body): his is an argument against behaviorism (there is a subtle but important difference in denying dualism in contrast to denying behaviorism). It seems to me like Alan Wallace exposed a category mistake in the making: Sean Carroll’s physicalist claim amounts to consciousness being a side effect (not unlike Ryle’s claim), an epiphenomenon, but that claim assumes a narrow set of tools available for empirical observation. If you grant introspection legitimate status as a tool for empirical observation (of the mind) – observations independent of the relations within which it is observable – it renders what initially looked like a category mistake (on Wallace’s part) – the dichotomy between mind and body – as irrelevant.

Even denying mind as observable phenomena (so denying mind-body dualism), without appealing to behaviorism, at a more abstract level, it is a category mistake to confuse things that can be observed and being – the focus on observability may be misguided because of its emphasis in the Buddhist practice of mindfulness meditation, which forces us down a false dichotomy.

Ordinary language philosophy, the underlying school of thought to which The Category Mistake traces its genealogy, is a philosophical methodology that sees traditional philosophical problems as rooted in misunderstandings philosophers develop by distorting or forgetting what words actually mean in everyday use. I could be understanding Ryle wrong, and I acknowledge I have very little exposure to his work or that of other exponents of this philosophy, but I have to think if you claim that much of philosophy amounts to (or emerges from) linguistic confusion then there is a baseline assumption of what constitutes everyday language use. The epistemological problem (or a chicken-and-egg situation, depending on how you formulate the problem) of knowing what can help guide the establishment of these guidelines remains open. The key to unlocking the legitimacy of exposing (or refuting) a category mistake, then, may often reside in the epistemic legitimacy of the propositions it is based upon.

Many thanks to my friends Eric Fixler, Tori Pintar, and Darshy for reading initial drafts, providing helpful feedback, and stimulating discussions.